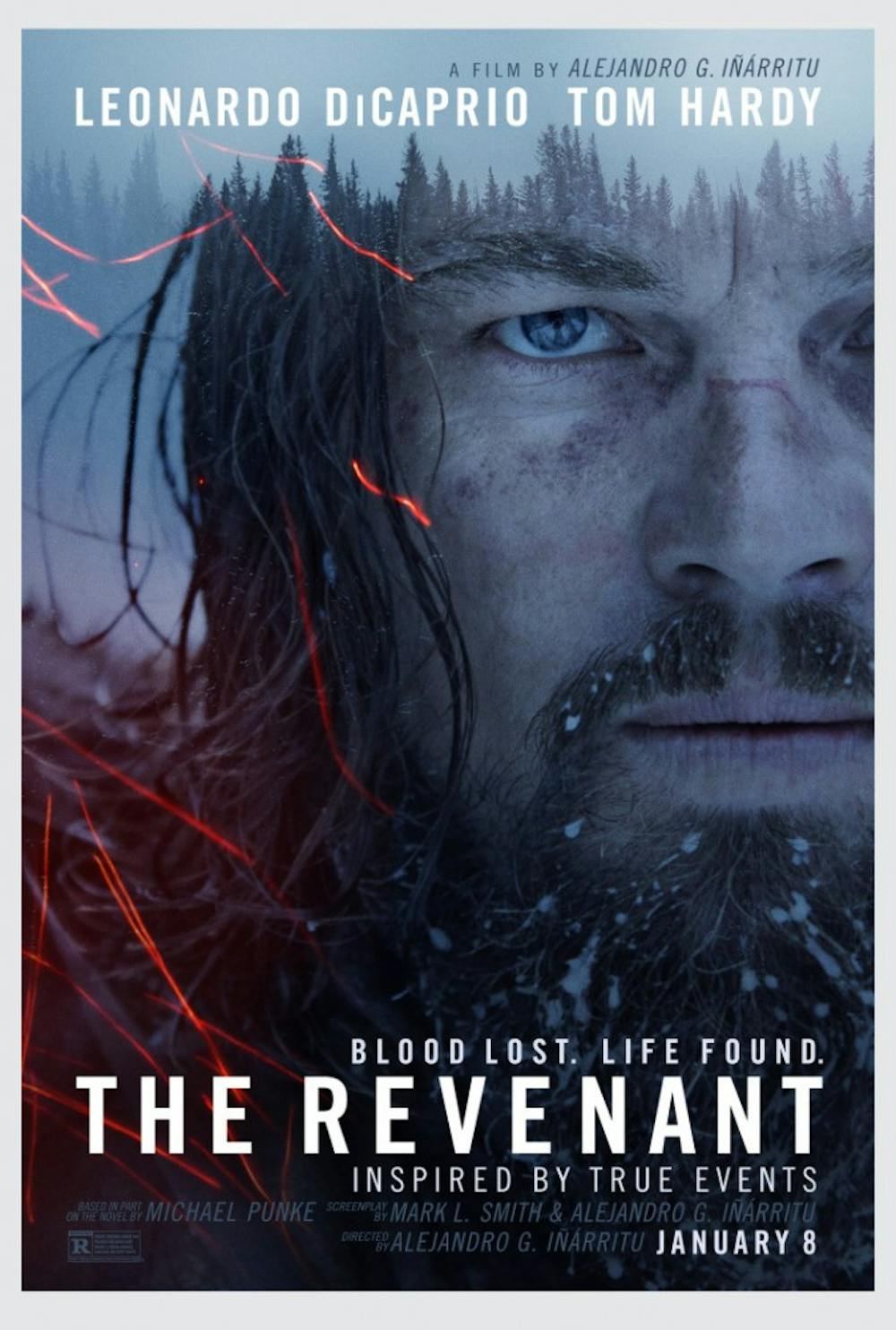

Hot Review: The Revenant

Opening December 25th

Towards the end of The Revenant, the main character, Hugh Glass is told: “Revenge is in God’s hands.” Glass states the phrase to himself again, at the end of the film, at the moment at which his time for revenge seems to have finally arrived.

Alejandro Inarritu’s The Revenant, set in a harsh pocket of 1820s American frontier, is certainly about revenge, but it focuses even more on duty, perhaps the real question raised by the advice given to Glass. What are our duties, and to whom are they owed?

For Glass (a bedraggled Leonardo DiCaprio) duty is owed only to Hawk (Forrest Goodluck), the son left to him by his deceased Pawnee wife, killed in a raid by American soldiers. When the film begins, Glass is helping an American trapping company navigate the northeastern wilderness, though it is clear he is motivated neither by money or patriotism - rather, a desire to feed himself and his child. Another trapper on the team, John Fitzgerald (Tom Hardy), is similarly disinterested in the good of the company, concerned strictly with paying down his own debts so he can move to Texas and start his life over. Only the Captain, Andrew Henry (Domhnall Gleeson) seems entirely devoted to his comrades.

These loyalties are tested after an Indian raid forces the group of trappers to return to camp. As they trek back, Glass is left on the brink of death following a violent bear attack (more like multi-stage cage fight), and the team must make a decision: leave Glass behind to die, or risk their lives by carrying him home and consequently, proceeding far more slowly. When the team is forced to climb a menacing, icy hill that can not be crossed with Glass in tow, Captain Henry, torn by duty to Glass and duty to the rest of his men, must make a compromise. For a bonus, some men must stay him with Glass until he dies naturally and give him a “proper burial,” while the others proceed back to camp. Hawk, Fitzgerald, and a younger, innocent-looking teenager, Jim, agree to stay behind. Once the others leave, Fitzgerald quickly takes control, and in a deceptive skirmish, Hawk is murdered and Glass is left for dead in an ominous incomplete grave.

Of course, there are far too many folk tales about the consequences of an inappropriate burial for the tale to end there. Glass tears himself from bindings that the team used to tie him to a plank (originally for transportation, later to prevent his escape) and crawls, terrifyingly, from the ditch, delirious and desperate to seek revenge at all costs; a zombie rising from the dead.

DiCaprio delivers his most chilling, visceral performance to date. Though he says very little throughout the entirety of the film, his mental state is clear at every moment through his impressive range of gestures and facial expressions. When Fitzgerald destroys his son, his eyes roll back into his head, his teeth appear almost to crack from seething. The pain and discomfort he demonstrates throughout the films seems simultaneously extreme and yet not exaggerated - the rumors that DiCaprio underwent hypothermia during filming for authenticity seem to hold up.

Hardy also succeeds as a believable villain; we deplore his poor morals, but we empathize with his desire for survival. When he tells Jim the story of how he was nearly scalped by an Indian, the account is distant, factual - Hardy’s Fitzgerald is not someone born evil, rather, a cold, violent world has chased the morals out of him. He says, at one point “Life? I don’t have no life. All I got right now is living.” Hardy’s character makes one believe that the final result of trauma is not readiness for death, rather, desire to live, regardless of the cost.

Perhaps the most fascinating characters in the film, however, are the various Native Americans. Duane Howard, who plays the head of the Sioux tribe, delivers an icy, dignified performance - it seems to mediate the bias surrounding both stories about Native Americans. Throughout the film, the Sioux are wild, ruthless, violent - their arrows tear through dozens of people without discretion, all for the sake of stealing furs. Their brutality is not necessarily elevated beyond that of the Americans, though it is also not sugar-coated; the film implies that neither side was above the excessive and ruthless violence that occurred at this time. That said, the Sioux are also played with a beautiful dignity. They wear strange, beautiful face paint and elaborately constructed hats and decorations made from various animal skins. Their eyes shine with wisdom, intelligence, and authentic human yearning. Elk Dog is devastated when his daughter is taken, he shifts all other priorities to the wayside until she is found. When Glass meets a lone Pawnee on his journey, the man protects him, shares his horse with him, and yet, is also blunt and honest: “You may die,” he says.

The film’s strongest quality, however by far, is its beauty. Cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki (Gravity, Children of Men) may be the best of his generation. The scenes of frozen, unexplored frontier are punctuated beautifully with countless shots of rushing water. Almost every action scene happens on the bed of a river or creek, creating a rhythm to the film of stagnation and dynamism. Fight scenes are done with rapid, continuous shots that immerse the viewer in the chaos, violence and death; making clear the true anarchy of war. The film opens with Sioux raiding Glass’s camp; men are impaled with arrows that seem to come from nowhere, the tension builds until the scene is overwhelmed with blood, fire and gunshots. Other scenes feature camera shots whirling upward towards the trees, creating depth; conveying the feeling of being swallowed by the wild. Still others combine violence and tranquility, simultaneously attesting to the brutality of the world and the power of the human spirit to persist. For instance, at one point Glass’s horse runs off a cliff and is killed by the fall. Desperately cold and hungry, Glass slices open his former steed, eats its entrails, and crawls inside its now empty stomach for warmth. When he emerges, it is as if the horse is giving birth to a full grown man.

At 156 minutes, Inarritu’s film is long, and at times feels slow. Yet, this is simultaneously its strength: it is contemplative, it requires the viewer to wait and reflect upon the visceral realities of death and life. Yet, it also supplies the violence and plot of any good action film: it is about Glass and his revenge, and yet refuses to focus on that at the expense of exploring the tangential story of the context in which his story occurs. It forces us to ask ourselves, in an anarchical world, to whom do we live for?

'The Revenant' opens for limited release December 25, 2015; wide release January 8, 2015.

More from The Rice Thresher

Worth the wait: Andrew Thomas Huang practices patience

Andrew Thomas Huang says that patience is essential to being an artist. His proof? A film that has spent a decade in production, a career shaped by years in the music industry and a lifelong commitment to exploring queer identity and environmental themes — the kinds of stories, he said, that take time to tell right.

Andrew Thomas Huang puts visuals and identity to song

Houston is welcoming the Grammy-nominated figure behind the music videos of Björk and FKA twigs on June 27.

Live it up this summer with these Houston shows

Staying in Houston this summer and wondering how to make the most of your time? Fortunately, you're in luck, there's no shortage of amazing shows and performances happening around the city. From live music to ballet and everything in between, here are some events coming up this month and next!

Please note All comments are eligible for publication by The Rice Thresher.