Learning to lead: Students reflect on whether the Doerr Institute’s coaching model can deliver results

The Doerr Institute for New Leaders is not a “coaching institute,” according to Associate Director for Coaching Holly Tompson — although it is only one of 12 initiatives, it is what many students have come to associate most with the institute.

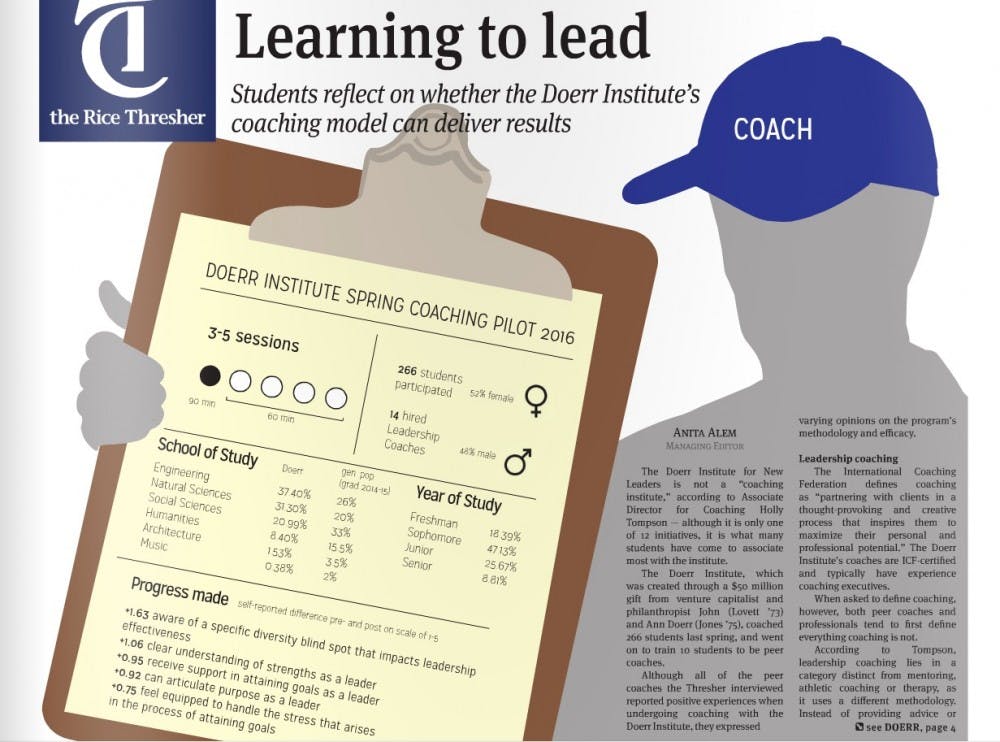

The Doerr Institute, which was created through a $50 million gift from venture capitalist and philanthropist John (Lovett ’73) and Ann Doerr (Jones ’75), coached 266 students last spring, and went on to train 10 students to be peer coaches.

Although all of the peer coaches the Thresher interviewed reported positive experiences when undergoing coaching with the Doerr Institute, they expressed varying opinions on the program’s methodology and efficacy.

Leadership coaching

The International Coaching Federation defines coaching as “partnering with clients in a thought-provoking and creative process that inspires them to maximize their personal and professional potential.” The Doerr Institute’s coaches are ICF-certified and typically have experience coaching executives.

When asked to define coaching, however, both peer coaches and professionals tend to first define everything coaching is not.

According to Tompson, leadership coaching lies in a category distinct from mentoring, athletic coaching or therapy, as it uses a different methodology. Instead of providing advice or mentorship, coaches use a method of inquiry.

Students typically attend three to five sessions lasting 60- to 90-minute sessions with their coach. Before the first session, students complete online pre-work informing their coach of any leadership goals they may have. They must also take an online “emotional intelligence” test, which quantifies characteristics like empathy and self-awareness.

Tompson said coaching can often look like guided goal-setting, where coaches help students move toward the goal that students themselves carefully choose based on their priorities. A portion of the first session is dedicated to analyzing the results of the EI test, and students may use the results as guides in forming their goals.

“Coaches are not giving students new activities to go get involved in,” Tompson said. “They say, ‘Let’s try to do this a little differently. Given that this is your goal, let’s fast-track your development.’”

The student is responsible for taking steps toward the goal and reflecting on the outcomes.

Tompson said leadership coaching can be particularly useful for Rice students because the organizations they are entering today are typically less hierarchical than they have been previously.

“Coaching gives you a better appreciation of your strengths as a leader and how you might be able to influence even if not in an official leadership position,” Tompson said. “In these flatter organizations, that’s going to be a lot more important.”

Assistant Director of Multicultural Affairs Jesse Hendrix, who is a certified leadership coach, said coaching is based extensively in psychology. Hendrix said the model draws on the idea that those being coached already have the solutions for overcoming challenges they face, so they do not need to be explicitly instructed or told what to do.

“If you come up with an approach to a challenge, you’re going to be a lot more inclined to make that happen,” Hendrix said. “If someone else says, ‘You should go do that’ and it’s not your idea, maybe you only put 50 percent into it.”

Joan Liu, a Jones College senior, said she found the relationship with her professional coach to be comfortable because of its confidentiality.

“I looked to [my coach] as almost an extension of myself, who I can freely bounce ideas off of,” Liu said. “There’s zero judgement, there’s no guiding, there’s no preset agenda. I just came in and talked and she would go through it with me.”

Selecting peer coaches

According to Tompson, the Doerr Institute partnered with the Center for Civic Leadership and the Center for Career Development to offer training to staff, alumni and a select group of students to become coaches themselves in the late spring.

There were about 22 total attendees, including faculty, staff, alumni and students. The program consisted of an ICF-required 60 hours of training.

The students selected as peer coaches were either part of the CCD’s Peer Career Advisor program or had previously held summer internships as part of Leadership in Professional Context (LEAD 150) and Leadership and Professional Excellence (LEAD 250). The latter is the class students take in conjunction with summer internships through the Leadership Rice Mentor Experience. These peer coaches were then responsible for coaching this year’s LEAD 150 and LEAD 250 students.

The CCL and CCD reached out to specific students for the peer coaching program, and ultimately selected 10; these students were then required to undergo leadership coaching as well.

Training: ‘I didn’t realize what coaching was’

Dylan Dickens, a Martel College junior, said students were paid $200 for attending all 60 hours of training.

Liu said although the training was long, she found the steps to be necessary, since they included outside reading and practice sessions.

“I was skeptical about coaching and then got so much out of it, so I [realized] it’s unfair for me to have a preconceived notion about coach training,” Liu said. “I tried to go into it with an open mind.”

However, Dickens said he lacked a full understanding of what the purpose of a coach is until he underwent leadership coaching himself.

“After just the first half an hour of training, it clicked with me how much I as a client almost wasted coaching,” he said. “I think Doerr needs to work a little bit on explaining to people what a coach is. And it’s really hard because people have preconceived ideas of what a coach is and is not.”

Martel senior AJ Barnes agreed he misunderstood the program, since he entered thinking it would be centered around mentoring students through their first internship experience.

“I didn’t realize what coaching was and I still don’t really know what it is,” Barnes said. “It’s different depending on who you talk to. I was very open [to students I coached] — ‘This is a brand new thing, I know about as much as you do.’”

Payment: ‘It’s an appropriate sum’

Tompson said Doerr paid peer coaches $15 to $30 per session depending on how much training they had undergone, to provide students an incentive to train the maximum 60 hours.

Brown College senior Adam Cleland said he found the payment to be appropriate for the work, especially considering executive coaches make hundreds hourly coaching C-suite executives.

“If you compare it to what my friends are paid to tutor seventh graders it’s an appropriate sum,” Cleland said. “For the amount of coaching that we went through, for the organization that we’re partnering with, it’s appropriate.”

However, Barnes said he felt the payment for the job, which is the most highest paying he has ever held, was unjustified, especially because he also worked as a teacher during the summer.

“I don’t think [coaching] is worth that much money,” Barnes said. “If it’s worth that much, then people who wake up at 5 a.m. and spend 12 hours a day molding people’s minds [as teachers should make more money]. People who work at the [Recreation Center], people who in my opinion are working harder, should be making a bit more.”

McMurtry College senior Sawyer Knight said since his summer peer coaching experience, he has moved onto coaching other students as well as professionals, in industries ranging from research to investment banking.

Coaching versus advising

Although peer coaches said the advice-free environment was helpful when they were being coached, some did not feel it was effective when they turned to coaching students themselves.

Cleland felt leadership coaching in its current form may not be as effective for college students as it is for executives, because it relies on students having the solutions to their challenges. He said he raised these concerns during training but was told to follow guidelines because the methodology works for students. The line between advisor and coach blurred for Cleland, especially when students had tangible questions on actions they could take to perform better at their internships.

“I believe college students don’t have the life experience to be able to find all of the answers inside of them,” Cleland said. “I knew it wasn’t going to work so I pulled my own strategy out. It was an altered strategy of coaching that needs to be implemented in the college coaching setting.”

Liu, however, said she strongly disagreed with the idea that students do not have the answer to their personal hurdles within them.

“I think that’s bullshit, that only CEOs have the answer,” Liu said. “Who are you to dictate what their own personal hurdles are, or what they need to do to make themselves a more effective person?”

Barnes said he similarly alternated between coaching and advising, and ultimately realized he prefers mentoring to coaching. To avoid conflicting with ethical guidelines forbidding coaches from doling out advice, Barnes would signal to his students at the end of a session when he was taking on an advisory role.

“I wanted to validate their feeling and say, ‘That’s a really great idea,’ which we were told not to say because it’s judging their idea,” Barnes said.

Tompson said although students who are being coached often want the coach to be an expert in their area and provide advice, this is not and should not be a requirement of coaching. For example, she said she often works with physicians, and is able to coach them successfully without herself being a trained physician.

“Does it help to know a little about their world?” Tompson said. “Yes, but would I ever try to give them advice on their world or say I understand their world? No. It’s a fine line.”

Being peer coached

Martel senior Neethi Nayak, who had an internship through LRME this summer, said she did not find her peer coaching helpful because she was at a personal career stage beyond that of her coach. She felt the coaching would have worked better if her coach had similar interests or were more familiar with her strengths and weaknesses.

“I felt like I was thrown into the peer-coach mentorship relationship without any background,” Nayak said. “There were already so many people I needed to touch base with, and this was just another person to touch base with.”

On the other hand, Brown junior Harrison Lin said he had a great experience with his peer coach, but felt it might have been because his coach took a more unconventional route. She did not ask any specific questions about leadership coaching or ask him to do pre-work.

“It’s like at the end of a long day, you go to your friend and you say, ‘This rocked, this sucked,’ and they just listened,” Lin said. “Through my talks with her, I was able to structure how I felt about work and how I could make the most out of it.”

Lin said despite his experience, he remains skeptical of leadership coaching in general.

“I’m not sure I’m inclined to seek out a ‘leadership coach’ because I’m not sure what that experience is like,” Lin said. “I don’t think I would go to the Doerr Institute.”

‘What society doesn’t need better leaders?’

Tompson emphasized that coaching is still only one of 12 strategic initiatives for the Doerr Institute, and only used as a tool to accomplish Doerr’s ultimate mission to develop leaders.

Peer coaches may coach freshmen as part of another initiative, the Leadership Development Navigator. Select LRME students from this summer will be trained also be trained as peer coaches.

The Doerr Institute is currently moving into coaching graduate students. Other programs like Rice Emergency Medical Services and Associate Dean for Health Professions Gia Merlo’s Medical Professionalism and Observership (NSCI 399) have specifically requested coaching.

Tompson said coaching is a resource for everyone, regardless of career interest or major.

“If every single sophomore wants a coach, we will provide it,” Tompson said. “We want to make sure it doesn’t seem like this is for businesspeople. What society doesn’t need better leaders?”

More from The Rice Thresher

O’Rourke rallies students in Academic Quad

Former U.S. Rep. Beto O’Rourke of El Paso, Texas spoke in front of the Sallyport to a sea of sunglasses and “end gun violence” signs April 17. The rally, organized by Rice Young Democrats, took place in the academic quad from noon to 2 p.m.

Uncertainty, fear and isolation loom over international students after visa revocations

With the wave of international student visa revocations across the country, including three students at Rice and two recent graduates, international students have expressed fears that their visas will soon be terminated without warning.

All bike no beer: bikers race remaining heats without spectators

Modified Beer Bike races, dubbed “Bike Bike,” were held at the track April 18 from 5-8 p.m. Results were released by email April 21.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication by The Rice Thresher.