Purity Test evolves, spreads beyond Rice

Have you ever done anything that you wouldn’t tell your mother? Lose 10 purity points. Ever told a lie? Ever cursed?

Don’t recognize these questions from the Rice Purity Test? That’s probably because you weren’t alive when the Thresher published the original version of the test in 1924. Back in 1924, the average score for the 119 women who took the test was 62. Of the scores collected on Dis-Orientation 2017, the Saturday after Orientation Week, the Houston average for people who took the test was 65. The number of tests taken in Houston spiked to 274 on Dis-O, from around 100 on a typical day.

"[The test has] latent, widespread and lasting impacts that can make new students uncomfortable."

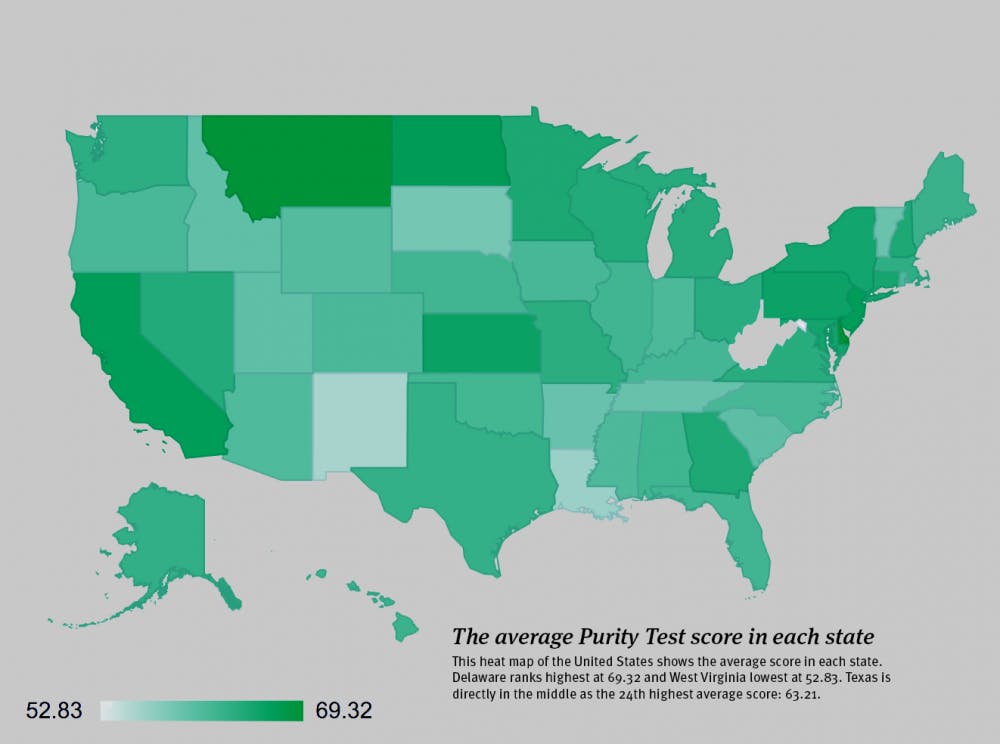

In just the past year the webpage of the “official” online version of the test, hosted by the Thresher, has been visited 1,524,204 times. The top city for purity test takers: Atlanta, followed by Houston, Dallas, Chicago and New York.

As the test spreads through colleges and high schools across the globe, inspiring chat rooms, blog posts and even an erotic book — “Bicurious and the Rice Purity Test” by Amy Morrel — it serves as an entryway into often taboo topics even as it is being phased out of the place where its current iteration was designed to be taken: Orientation Week.

Spread

When Madeline Cook first heard of the test at St. Agnes Academy, a private all-girls’ Catholic School in Houston, her friend told her one of the smartest girls in their grade said she had gotten a 19.

“I was like, ‘What the heck what test would she get a 19 on?’ and then I pulled it up and I was like, 'Oh this is not what I was expecting,'” Cook, now a sophomore at Drexel University, said.

Cook said that being at an all-girls’ school made it a lot easier to share scores.

“It would have been really awkward to be like, ‘Oh yeah I heard this person got like a 15 if there were a bunch of boys around because then they would have been like, ‘Wow, that girl is a slut,’” Cook said.

While most girls wanted to have scores in the middle range, Cook said going to a Catholic school made higher scores less embarrassing. After sharing scores, girls often delved into the details.

“If you were friends you would talk about the details or it would all come out later in a game of ‘Never Have I Ever’ because you now had new targeting information,” Cook said.

At St. Agnes’ brother school, Strake Jesuit, the purity test spread when the school gave every student an iPad.

“There was a period of a few weeks where it was super popular and everyone took it to goof off in class, but eventually everyone kinda got over it and moved on to the next internet fad,” Logan Baldridge, a Duncan junior, said.

Like Cook, Baldridge said the attending an all-boys’ school made students more comfortable sharing their scores.

The test also reached Bellaire High School, a Houston public school, according to Andy Zhang, a Jones College senior. He said that the score became part of a student’s social status in high school, but Rice students cared much less about each other’s scores.

“We did take the test early in freshman year and it was a similar feeling as taking it in high school but that feeling quickly dissipated,” Zhang said.

Other institutions of higher learning are also taking the purity test. On the East Coast, one university is at least partially responsible for the purity test’s popularity in Atlanta, Georgia: the Georgia Institute of Technology. Joshua Santillo, a student in his third year at GT, said several people in his residential hall knew about the test and asked about “RPT scores.” A week into the semester, Santillo said the hall had a designated large classroom-sized whiteboard for students to self-report scores.

The test has also spread south to Florida, reaching Lena Daniels and her friends at the University of Central Florida.

Daniels, a sophomore, decided to write a blog post titled “Shaming the Rice Purity Test” on media website Her Campus after taking the test with a group of friends at UCF.

“I just think the general idea that you're put into these categories is a little bit judgmental,” Daniels said. “It can lead to judgmental things.”

However, Daniels said she would not discourage others from taking the test and continues to do so herself.

“I would say take it if you want to take it because it's something curious to find out about yourself,” Daniels said. “Every once in awhile I still take it, I'm like, 'Have things changed?' Just know that it's just a test, it's just a number, it doesn't define who you are as a person, it's just a very small factor of life.”

“Shaming the Rice Purity Test” is Daniels’ most popular article, receiving as many as 20,000 views each month.

“I've noticed since then other people have started writing about it,” Daniels said. “It has become more of a conversation topic lately.”

History

The original 1924 purity test, which was only given to women, featured questions reminiscent of another era. “Have you ever been engaged and broken it?” the test inquires. Two questions have survived the test of time since their inception 93 years ago: “Have you ever cheated?” and “Have you ever been drunk?” 58 of the 119 original respondents said they had cheated. Only four said they had ever been drunk.

“[Freshman women] in truth do come to college young and unsophisticated, and they become demoralized year by year,” the article presenting the 1924 test said.

The 10-question test resurfaced 50 years later in a 1974 issue of the Thresher. The editorial staff included a slip for readers to cut out, fill out and mail in, but the results of the survey were never published. A reference to the purity test appeared in a 1980 “misclassifieds,” a precursor to the Thresher Backpage. The misclassified advertised “The First Annual Rice Purity Contest” where each couple competing would receive a copy of the test, an initial score of 100 and the challenge of having the lowest combined score by sunrise.

In 1988, the Thresher ran a purity test vastly different from the earlier version. The Backpage suggested a new rule for the purity test: “If you don’t understand the question, add two points.” The new version of the test featured 100 questions, each worth one point, as opposed to 10 questions each worth 10 points. In its introduction the test defined the acronym “MOS” as meaning “member of the opposite sex.” The test separated out questions regarding homosexuality, placing them lower on the list of questions. In the purity test, activities considered more licentious are towards the bottom of list. Alarmingly, the test also included questions about sexual crimes including child molestation and statutory rape.

By 1998, all mentions of molestation and rape had been edited out and the acronym “MOS” was replaced with “MPS” meaning “member of the preferred sex.” Many of the questions in the 1998 version are included in the current version, including the 69th question (“?”). However, the question “Used alcohol to lower an MPS’s resistance to sexual activity?” remained and several questions regarding homosexuality and members of the same sex were featured in lower questions of the test. The 2008 test also included questions about using alcohol to lower inhibitions of sexual partners and many of its questions are undeniably cruder than the current version. However, the final question, a position reserved for the most egregious act, stood in stark contrast to the rest of the test: Have you ever neglected to wash your hands after using the restroom?

In 2011, the Thresher Backpage editors refused to publish the test, citing its divisive nature of separating students based on score. In 2012, however, the same editors decided to run the test due to what one editor, Anthony Lauriello, wrote was its positive potential of allowing O-Week groups to “transition from the rosy summer camp feel of O-Week to the somewhat irreverent year ahead.” If Lauriello and his fellow editors did not run a new test, he argued, O-Week groups would take older versions containing sexuality bias in its separation of homosexuality as well as non-consensual sexual activities.

Those backpage editors created the version we know today as the Rice Purity Test, the version that can be taken at www.ricepuritytest.com.The site receives more hits than rice.thresher.org and also makes the Thresher more money than their own website due to the range of test takers it attracts, both in age and location.

O-Week/Debate

The purity test has long been a staple of O-Week, and yet for decades the debate over whether to introduce new freshmen to the questionnaire has waged on.

David Rhodes (Will Rice ’97), now president of CBS news, expressed his opinion in a 1995 issue of the Thresher. He said that too often, advisors treated freshmen like their children, dependent upon the wisdom of upperclassmen for college survival. Rhodes coined these advisors “The O-Week Gods” and wrote that many disapproved of O-Week groups taking the purity test, which he viewed as “already overrun with political correctness.”

“Could it be that the purity test is a harmless college right-of-passage meant to separate the men from the boys (sorry, the Members of the Preferred Sex from the Less Inhibited Members of the Preferred Sex?),” Rhodes wrote.

Ten years later, Pulitzer prize finalist Evan Mintz (Hanszen ‘08) wrote about how in college students are free to work for themselves, “Whether it is through that 4.0 GPA representing how much you’ve learned or that purity score of 4.0 representing how crazily you’ve partied.”

Eric Rechlin (Will Rice ‘04), who took the test with his O-Week group in 2000, said one of his advisors read the test out loud while the rest of the group kept track of their scores. At the end of the test, the group shared their scores with some members volunteering additional details. Rechlin said that although taking the test put him outside his comfort zone, he believes it should remain a part of O-Week.

“In some ways, that's part of what O-Week is about, and in hindsight I am glad they did it,” Rechlin said. “Introducing students to things that make them feel uncomfortable is absolutely a critical component of a university education to help them grow as a person and prepare them for the real world.”

In a 2005 issue, the Thresher reported on a “tamer O-week” where the Purity Test was banned after the coordinator said the test could constitute sexual harassment. This year, the Jones College O-Week coordinators banned the Purity Test from Jones’ O-Week. O-Week advisors were not permitted to take the purity test with their new students during O-Week.

“The purity test goes against just about every major value we identified for Jones O-Week 2017,” Jones O-Week coordinator Evan Toler said. “Although most people may seem comfortable in the moment while taking the test, there are latent, widespread, and lasting impacts that can make new students uncomfortable and self-conscious about what they have or have not done.”

Toler, a senior, said the test separates winners and losers and gives the appearance that certain activities are normal at Rice, fueling the imposter syndrome felt by Rice students.

“As a senior, the purity test still makes me uncomfortable, and I would never encourage anyone to have to take it and have to experience the same feelings that I felt right after O-Week,” Toler said.

Lovett Coordinator Akin Bruce said that advisors shouldn’t hide the purity test from new students, but rather wait until after the chief justice and Healthy Relationships talks. Meanwhile, Will Rice advisors mentioned the Purity Test during O-Week in the Healthy Relationships Talk.

Will Rice Coordinator Carey Wang said they cautioned new students against viewing the test as a checklist of experiences they should have at Rice.

“We have advisors with a diverse range of “Purity Score[s]” and we want to emphasize that everyone can be successful and involved at Will Rice regardless of what they have done on that list.”

Amelia Calautti, a Will Rice freshman, took the Purity Test with her O-Week group. She was initially worried that she would be judged for her score being too high or too low, but ultimately enjoyed the experience.

“After sharing our numbers and seeing a whole spectrum of scores, I no longer felt like I should be ashamed and it really was just a good laugh for my group and I,” Calautti said. “The activity made me realize that no one actually cares about your purity test score and that everyone comes into college with different experiences.”

More from The Rice Thresher

Andrew Thomas Huang puts visuals and identity to song

Houston is welcoming the Grammy-nominated figure behind the music videos of Björk and FKA twigs on June 27.

Live it up this summer with these Houston shows

Staying in Houston this summer and wondering how to make the most of your time? Fortunately, you're in luck, there's no shortage of amazing shows and performances happening around the city. From live music to ballet and everything in between, here are some events coming up this month and next!

Rice to support Harvard in lawsuit against research funding freeze

Rice, alongside 17 other research universities, filed an amicus curiae brief in support of Harvard University’s lawsuit against the Trump administration over more than $2 billion in frozen research grants.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication by The Rice Thresher.