What is virginity, anyway?

A Research Methods study explores attitudes towards virginity throughout the sexuality spectrum at Rice.

It turns out that Rice students are pretty good at guessing how many of their peers are virgins: 44 percent was the true number and 39 percent the average estimate, according to a recent Research Methods (SOCI 381) study. Study team member Eric Shi said this result surprised him most; he thought Rice students would underestimate the number of virgins.

The group was made up of students Thresa Skeslien-Jenkins, Bharathi Selvan, Navya Kumar, Ami Sheth and Shi. They aimed to study the origins, definitions and perceptions of virginity on campus.

“What is more taboo [than hookups on campus] is this concept of virginity, something your mother firmly believes in but you think is wonky. Or do you?” Kumar, a Hanszen College junior, said. “That question was essential, and our findings illuminated the legacy of the more conservative view as well as the more liberal notions of choice and autonomy.”

The group collected survey responses from Oct.18 to Nov. 1. They received 809 responses and used 692 that were complete or majority-complete responses. The survey yielded a sample of virgins and nonvirgins who expressed their views on virginity — including whether or not it exists at all.

The survey first asked how respondents would define losing one’s virginity. For example, could oral sex count? What about penetration with a dildo or other object? After breaking down responses by gender, the group found that women tended to think a broader range of activities constitute loss of virginity while men were less likely to choose oral sex or penetration by objects.

“We assume that's because [men] don't have a vagina so they have no interest in that form of losing virginity,” Skeslien-Jenkins, a Martel College junior, said. “If they were to insert something else into a woman, they would not themselves feel that they lost their virginity, whereas women would feel differently.”

Overall, the group was pleasantly surprised by the number of people who chose non-heteronormative definitions of losing virginity, including anal and oral sex.

“I think LGBTQ and straight people alike consider the penetration of a vagina by a penis to be, for broader society, how you lose your virginity, but we had to have straight people accepting anal and oral sex [as methods for losing virginity] for that number to be so high,” Skeslien-Jenkins said. “I do think it's good and it's a lot better than what would have been done in the early or middle-2000s.”

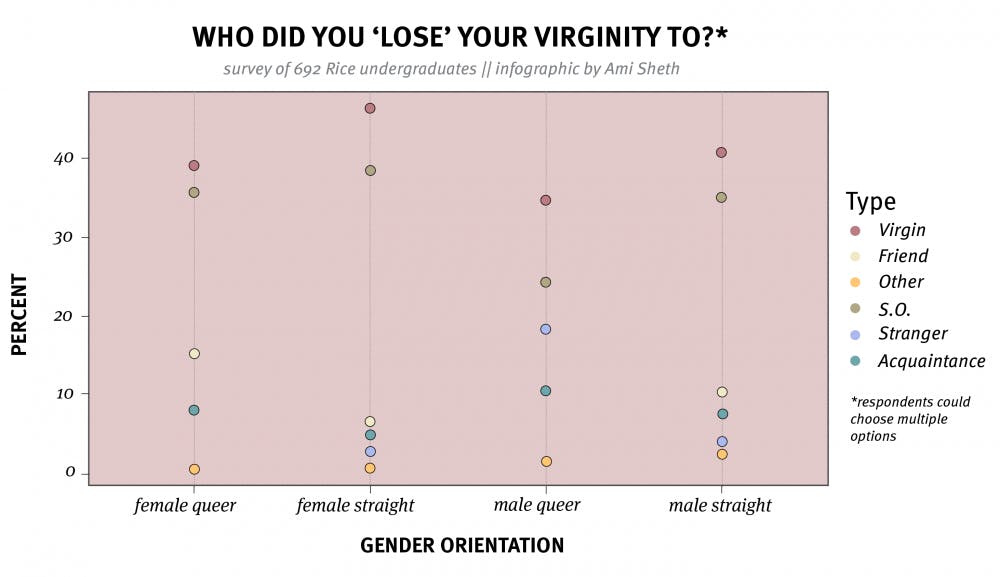

The group also broke down the results by sexual orientation (using the terms “straight males,” “straight women,” “queer males,” and “queer women”) to see how perceptions varied based on the type of sex respondents might have had or potentially are having.

“There are nuances to our understanding of virginity and those understandings can vary based on identity,” Sheth said. Straight males, for example, were the least likely to stray away from the definition of losing virginity as the penetration of the vagina with a penis. Another interesting result was that only 75 percent of queer males selected anal sex as a way to lose their virginity. Skeslien-Jenkins hypothesized that because virginity has historically been defined as a heterosexual concept, some queer men might think that if they only ever have anal sex, they will never lose their virginities—-or they may think they were never virgins in the first place.

Respondents also had the option to write in their own definition. One wrote, “The first time you are completely physically vulnerable with another person.” Another respondent wrote, “As intimate as you can get with another person.” Several others, including queer males, responded that virginity was a social construct rather than defining it using the survey categories. Skeslien-Jenkins said that choice might have contributed to the relatively low number of queer males who chose the anal sex option. There was no option in the survey for a respondent to indicate whether or not they believed virginity existed at all.

Queer men also stood out in the results as the least likely to wait to have sex with “the right person.” Only 70 percent of queer men--both virgins and nonvirgins--said that, ideally, they would wait, compared to 85 percent of straight women, 81 percent of queer women and 75 percent of straight men.

“What we hypothesized about that is that for queer men, it’s really difficult to find a person and especially to find that first partner, and so it’s often out of convenience,” Skeslien-Jenkins said. “I personally have talked with queer men [who have said], ‘I want to know what that response was because I feel like I’m the only one who lost their virginity to a stranger.’”

In addition to asking respondents what virginity is and what they would consider before losing their virginity, the survey also asked who they would tell after they had done the deed. The group found that women were more likely to tell someone, and straight men were the least likely to tell someone. Skeslien-Jenkins attributed the difference to the fact that women tend to be more expressive, while men might be hesitant to tell someone they have lost their virginity because it would reveal that they had been a virgin all along.

“In our survey we found that men were describing [virginity] as shameful a lot more than women,” Skeslien-Jenkins said. “[There was this] idea that once you get over it, you're a lot more proud.”

Not all straight men were so shy, however. When asked who he told after losing his virginity, one straight male respondent simply wrote in, “Twitter.”

Part of the survey asked respondents to select words that they associated with virginity, based on a theory by Vanderbilt University associate professor of sociology Laura Carpenter, called “the three scripts” of describing virginity: gift, stigma and process. Each response was coded as either gift, stigma or process. “Womanhood,” for example, was coded as process, whereas words like “embarrassing” were coded as stigma.

"According to Carpenter, women are more likely to see [virginity] as a gift, something they want to give to someone, something they treasure and keep for someone special,” Skeslien-Jenkins said. “Process is more likely to be applied to LGBT people and those that don't value the idea of 'purity' and see losing their virginity like it's a rite of passage, it'll happen when they're ready, and not really keeping it at the forefront of their mind. Stigma is usually applied to men and is the idea is that it's shameful or embarrassing and something to get rid of.”

The group found that the most popular word associated with virginity was “choice,” followed by abstinence and then sexual restraint. Selvan and Sheth said that Rice students aligned with the three scripts Carpenter described, but less strongly than they expected.

“This theory is much more nuanced at Rice,” Selvan said. “Students fit into more than one script and they don't always fit into the existing theories either.”

Sheth said that the word associations showed that women at Rice didn’t think of virginity as a gift as much as they did in Carpenter’s study.

“Women are changing their perception of virginity from a gift to a process, so less wanting to be in love or wanting it to be special before losing their virginity to more just feeling ready,” Sheth said.

Kumar said that she thought students would deviate further from the three scripts than they did.

“Honestly, I expected Rice to be very ‘virginity is a social construct and this survey is dumb and patriarchal and backwards,’ but we got a lot of responses indicating it was in fact meaningful and a choice and a decision that is not made lightly,” Kumar said.

According to Skeslien-Jenkins, the team hopes their findings can be used to change conversations surrounding virginity.

“Right now there's a lot of sex education around abstinence and connected to the idea that if you are not abstinent, you are less than someone else,” Skeslien-Jenkins said. “We really want to take away the worst from the idea of virginity so we can emphasize it's a choice that you make and it's empowering, but it has no impact on you as a person or you in society.”

More from The Rice Thresher

Five international visas revoked at Rice

Federal authorities have revoked visas for five international affiliates at Rice — three current students and two recent graduates, President Reginald DesRoches announced in an April 11 message to campus. The revocations are “not related to social activism or protests,” a university spokesperson told the Thresher.

Modified Beer Bike races rescheduled to April 18

Beer Bike races have been rescheduled for April 18 at 5-8 p.m. The makeup event was announced in an email to Beer Bike captains, coordinators and stakeholders, from the campuswide coordinators and the Bike Captains Planning Committee.

Good Friday and college night overlap sparks ire among students

Four college nights are happening on Good Friday this year. This overlap has caused controversy amongst students who observe the high holy day.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication by The Rice Thresher.