Menil collection unveils first Aboriginal art exhibit

Friday the 13th marked the inauguration of the Menil Collection’s most recent and least-precedented show: “Mapa Wiya (Your Map’s Not Needed): Australian Aboriginal Art from the Fondation Opale.” The beloved de Menils’ legacy of pushing their city’s artistic and political limits is continued here as this is Houston’s first exhibit dedicated exclusively to Australian Aboriginal art according to curator Paul R. Davis.

A special preview of the collection on Wednesday, Sept. 11 brought in representatives from the Australian consulate, as well as Teresa Baker, one of the artists whose work is featured prominently in the space. Though the event was modest, it provided a thorough survey of the more than 100 works and even invited Baker and her translator to speak on their art and culture.

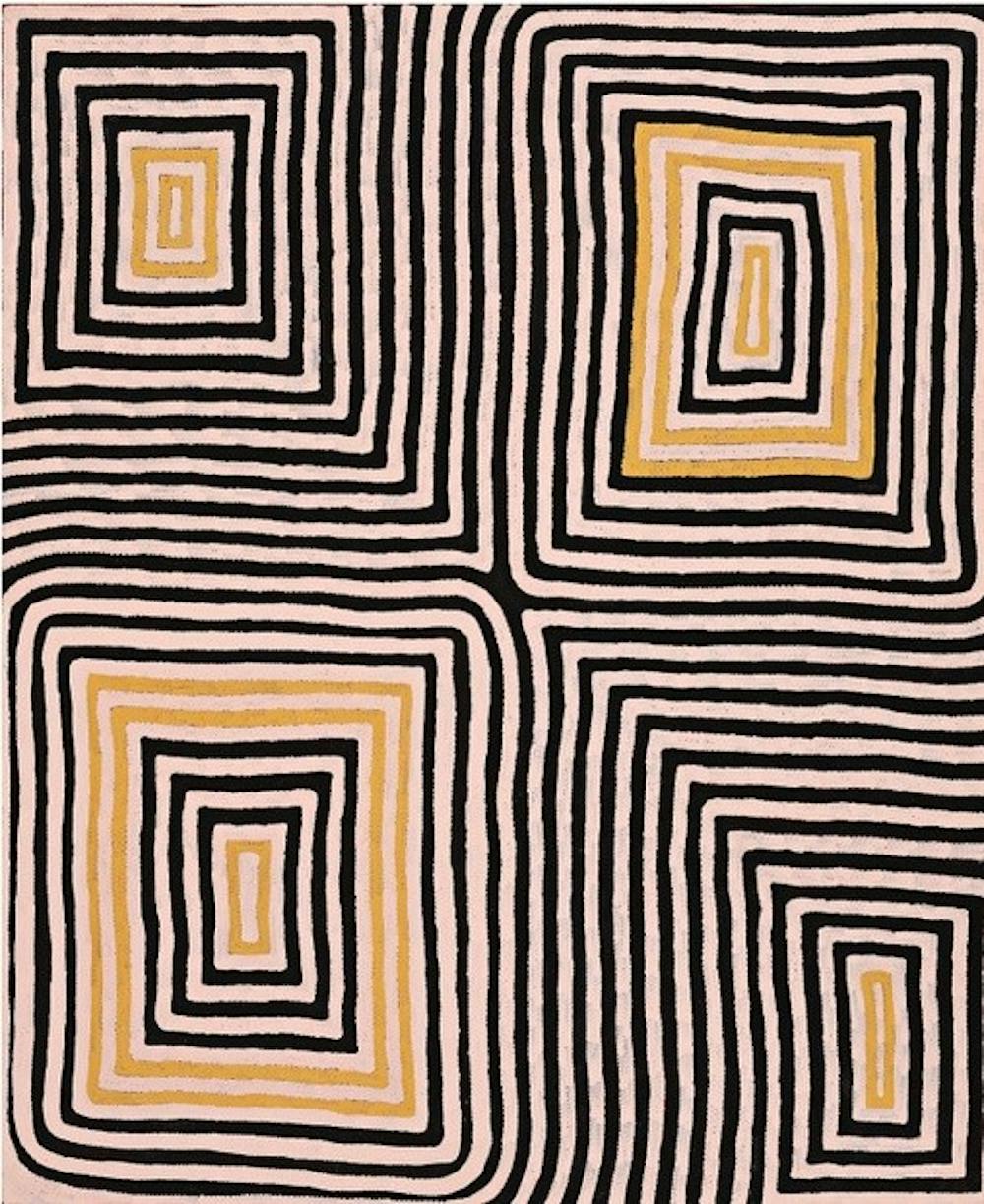

The collection encompasses a variety of vibrant paintings, shields, hollow log coffins and pieces of engraved mother of pearl. Such breadth in material is matched by the range of artists featured. Several pieces were created collaboratively, including the monochromatic, large-scale canvases that Baker and a collective of women from her community composed.

Others are the works of individual artists, many of whom are internationally acclaimed and whose contributions to modern art are in dialogue with parallel modernist innovations. Emily Kame Kngwarreye’s dreamy, dappled lines, for example, influenced the proto-conceptualist Sol LeWitt. This detail from the tour may go unnoticed, but when considering the collection’s position alongside other iconic modern and contemporary artists, “Mapa Wiya” asserts Aboriginal art’s relevance to a larger artistic canon. The exhibit refutes the atemporality and isolation in which indigenous art is typically viewed; “Mapa Wiya” takes up its own space while simultaneously remaining in conversation with a larger visual history.

United by the thematic and ubiquitous concept of Country — the crucial foundation for the autonomous ways of Aboriginal peoples — “Mapa Wiya” gives platform to the diverse ways Aboriginal artists practice, conserve and share their knowledge of Country. With stylized depictions of the land’s terrain and visual representations of cultural stories and laws, every piece reiterates what Baker and her translator shared with her audience: “We know our country.”

This is perhaps best embodied by the exhibit’s namesake: a recent drawing by Kunmanara (Mumu Mike) Williams. Meaning “no map” in the Pitjantjatjara language, his appropriation of official government materials challenges the imposed and arbitrary cartographies of his Country. Williams’ works are the first to greet viewers in the gallery space, confronting them with his declaration of rejection and agency: “Your Map’s Not Needed.” Suddenly, the space is not quite the Menil’s anymore; it houses precious iterations of Country, therefore becoming, for an instant, Aboriginal domain.

Such an adamant denial of British constructions of knowledge is inherently political. Indeed, the collection’s specific focus on pieces made after the 1950s, during which the Aboriginal civil rights movement was occurring, suggests an interest in Country as a means for political and cultural reclamation and reckoning.

Two particularly memorable works address the elephant in the room which the Menil treads around cautiously: the pillaging of indigenous land and peoples at the hands of the British. “Bedford Downs Massacre,” by Rover Thomas features clusters of circles huddled within dotted borders partitioning the canvas. The painting memorializes a chilling episode from 1920 colonial Australia in which two Aboriginal men were poisoned, clubbed and then burned. In the same room, a striking forest of hollow log coffins has been erected. Larrakitj, lorrkon or dupun consist of hollowed out and painted tree trunks in which the bones of a deceased clan member are placed. The surfaces are then etched with patterns and painted red, yellow and black. The curatorial decision to group these renditions of burial art beside “Bedford Downs Massacre” speaks to the mass murder of Australian Aboriginal peoples. Importantly, it also speaks of cross-generational teaching — of a material culture that embodies the concept of memory as resistance. In both works, past individuals receive a second body and are thus kept alive — keeping, in turn, Country alive.

The geometric patterns and vibrant stippling that make up this visual language of Country may be tempting to code as “abstract,” but examples such as the ones above serve as reminders that, in reality, what we are witnessing is narrative inaccessible to non-aboriginal audiences. The Menil can only truly remove the first layer of varnish. Staff members were frank in their acceptance that they cannot claim to be aware of all the nuances present. Still, it is a strength and beauty that one need not be privy to in order to appreciate. “Mapa Wiya” celebrates Australian Aboriginal Country in its own terms and prompts pressing questions relevant to modern discourse surrounding post-colonization — questions of how indigenous knowledge is conserved and shared today, questions of land occupation and even questions of art acquisition, as the collection is permanently held in Switzerland by the Fondation Opale.

These questions — just as these cultures and their art — are not static, nor are they to be confined to history. They are very much alive today, something the Menil Collection further celebrates with “Mapa Wiya.” Check your settler-colonial baggage at the door and make sure to stop by before Feb. 3.

More from The Rice Thresher

Study Abroad Photo Contest spotlights global experiences

For the first time since the Covid-19 pandemic, students gathered in the Ley Student Center to celebrate global experiences through photography.

Review: "The Crux" Should Redefine Djo

Joe Keery’s work has been boiled down to Steve Harrington from “Stranger Things,” but this label shouldn’t define his 10 years in the entertainment industry. Keery, under his stage name “Djo", is the voice behind the TikTok hit “End of Beginning,” which was released with his album “DECIDE” in 2022 and climbed the charts for the first time in 2024. With “The Crux”, Keery’s third album, he tries to separate his work as Djo and an actor, evidenced by the album’s visual of Keery escaping a building.

Review: “Lonely People With Power” merges blackgaze fury with dreamy introspection

Fifteen years into a storied career that’s crisscrossed the boundaries of black metal and shoegaze, Deafheaven has found a way to once again outdo themselves. “Lonely People With Power” feels like a triumphant return to the band’s blackgaze roots, fusing massive walls of guitar-driven sound with whispery dream-pop interludes, recalling their classic album trio of the 2010s (“Sunbather,” “New Bermuda” and “Ordinary Corrupt Human Love”). It also bears the learned refinements of “Infinite Granite,” the 2021 album where they dabbled more boldly in cleaner vocals and atmospheric passages.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication by The Rice Thresher.