Touchable Gods: Winningham photography exhibit resurrects Houston’s ringleaders

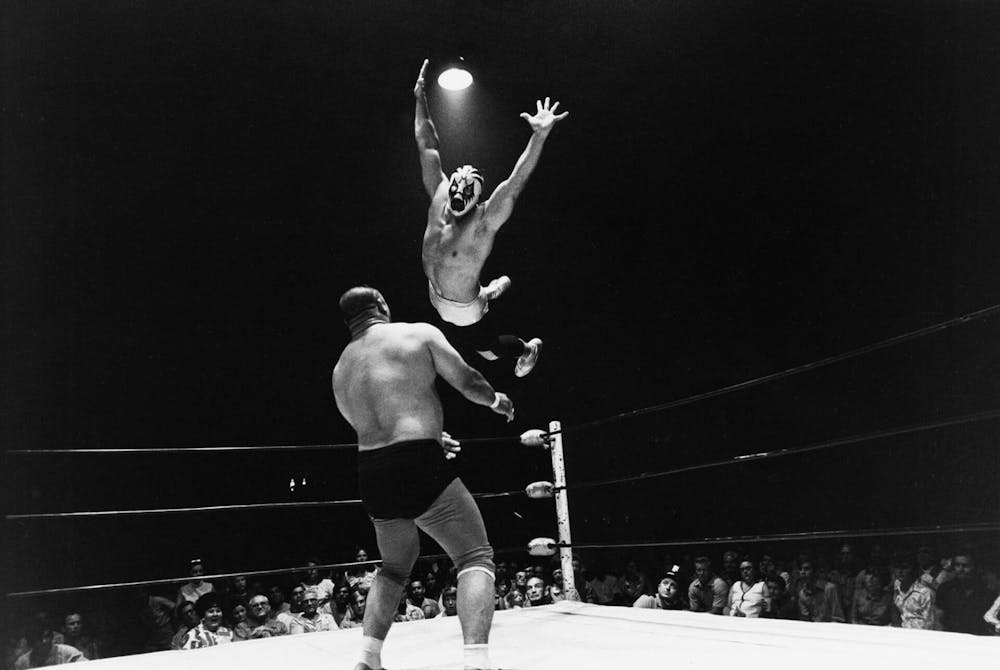

In a city as sprawling and teeming with life as Houston, crowds have an energy, a vitality and a gravity of their own. Photography professor Geoff Winningham (Baker College ’65) knows this. He’s known this since 1971, when the young photographer found himself caught in the gravitational pull of the Houston Coliseum. There really couldn’t have been a more fitting title for the arena where men performed Roman-esque choreographies of combat, bathed in light and enveloped by the shouts of supporters and slanderers alike. Now nearly 50 years later, wrestling fans and photography enthusiasts alike are able to get another look into the ring with the opening of Winningham’s exhibit, “Friday Night at the Coliseum,” the first comprehensive gallery exhibition of his internationally renowned body of work.

The work in the exhibit, which opened last Saturday, was originally published in 1971 in book form and contained photos from over 170 rolls of film. Though Winningham admits this first edition didn’t sell particularly well among the wrestling community, the book received immediate critical acclaim in the art world, earning a special six-page spread in Life magazine titled “The Rousing Rebirth of ‘Rasslin.” Since then, the work has come to be considered a cornerstone achievement of contemporary American photography; six photographs from ‘Friday Night at the Coliseum” concluded the American Federation of Arts’ 1973 publication “Masters of the Camera,” a collection of the most important American photographs of the 20th century.

The exhibit coincides with the release of the second edition of “Friday Night at the Coliseum,” a remastered collection of the project. The edition features previously overlooked photos and omits photos Winningham no longer likes. He also includes quotes from writers who offer illuminating perspectives on the often misperceived nature of professional wrestling. A quote from French critic Roland Barthes introduces the second edition of “Friday Night at the Coliseum” and adorns the Rice Media Center gallery wall: “What is thus displayed for the public is the grand spectacle of suffering, defeat and justice. Wrestling presents man’s suffering with all the amplification of tragic masks.”

“I don’t like to ever suggest to somebody in advance how they should look at my photographs,” Winningham said. “But it does help to have such a learned and thoughtful idea about it before you get to the pictures. This is not ‘fake sport.’ This is serious, grand spectacle.”

When Winningham saw masked men flung through the air and heard the passionate shouts of wrestling fans on those electric Friday nights, he knew he was about to capture something special.

“It was one of those subjects that I thought okay, I’m not sure anybody’s ever seen this properly, has ever really written about it or photographed it or observed it for what it is,” Winningham said. “It’s, in my mind, a folk theater where people come to experience a dramatic presentation, a spectacle in which good goes against evil and doesn’t always win, but is always worth cheering for.”

The contorted faces and bodies of grown men in the pain of defeat or elation of victory decorate the walls of the Media Center gallery. In addition to the action shots, many of Winningham’s black and white photographs capture the palpable anxiety and anticipation of the audience, suspending the excitement noticeably plastered on the faces of young fans swarming to get a fighter’s autograph in one photo. In others, it seems that the spirit of ferocity spills outside the ring, infecting older women with an emboldened fearlessness as they shake their fists and shout at the men twice their size. In a black and white video recording displayed on a small television in the corner of the gallery, an old woman raises her arm above her head, threatening to lash out at the giant lumbering past her.

“When [the fighters] were in the ring, they were god-like,” Winningham said. “But when they were coming into the ring and when they were coming out, they came right through the crowd, and the crowd could touch them. These guys were touchable gods.”

On the second floor of the gallery are a series of photos all taken during one memorable showdown: Chief Wahoo McDaniel and a masked man known as “Mr. Houston” locked in a Russian Chain Match, a fight in which the two competitors are tethered together at the wrists with a chain. The photographs chronicle the brutal match as McDaniel’s blood-smeared face twists in pain with each slash of the chain against him until he delivers the finishing blow to Mr. Houston, an unforgiving reverse Tomahawk Chop. The audience cheered exuberantly for their local hero, for this was no ordinary victory; it was a symbolic one, as the Choctaw-Chickasaw Native American triumphed over the masked villain, a self-proclaimed Russian scientist, in a metaphorical feat of American supremacy. In a nation steeped in the Cold War and still reeling from wartime, the wrestling ring in 1971 was where social and cultural tensions that proliferated American society, unseen and insidious, could be battled out with an immediate viscerality without political or militaristic consequences.

“It was a locally promoted folk art in which the spectacle reflected the concerns and issues in the air around that time and that place, so the people were passionately involved,” Winningham said. “Whether it was ‘real’ or not was really not an issue. The point is it was celebratory and cathartic to go there.”

The act of going to the Coliseum for a wrestling match was an act of community solidarity, evident in the racial and gender diversity of the crowds captured in Winningham’s photos. While the phenomenon of local wrestling is gone for now — effectively dismantled by the rise of a national market for dramatized, televised wrestling — Winningham’s work has adopted the role of the Coliseum itself as a site where people can gather and remember a deeply Houstonian and American tradition.

Among the throngs of people marveling at the photographs on Saturday night, tangible nostalgia and camaraderie one might expect at a high school reunion pervaded the atmosphere. Bridget Langdale, a native Houstonian who attended the exhibit opening, said she had gone to high school with the children of referee Danny McShain and promoter Paul Boesch, both subjects of Winningham’s work and fixtures of the Houston wrestling scene.

“It has been so much fun to go and look at this exhibit and then look at someone standing next to you and go, ‘Were you there? Did you see it?’” Langdale said. “That’s probably the most awesome part, because this is our history. I was talking to a couple of people, they overheard me talking and they walked up and said, ‘I think we went to the same high school together.’”

The exhibit is a celebration of two 50th anniversaries: the 50th anniversary of the Media Center and the 50th anniversary of Winningham’s tenure as a Rice professor. His return to Rice after graduating in the early 1960’s coincided with the construction of the Rice Media Center the following year, and since then the photographer’s legacy has been intimately entwined with the history of arts at Rice.

“I hate to see the building go. I’ve worked here all of my working life. Not only that, but I love the building,” Winningham said. “The Media Center has always been, from the beginning, a place where Rice met the community. So the place has an important history, and of course it’s personal history to me as well. It feels great to have [the exhibit] here. I’m showing it at home. This is where it belongs.”

Through the exhibition at the Media Center, Winningham has chosen to house his first comprehensive exhibition of his most famous work at Rice as opposed to a museum. His choice emerges as a poignant presentation of an artistic endeavor come full circle, and a heartfelt goodbye to the place that started it all.

“Friday Night at the Coliseum” is on view now at the Rice Media Center central gallery until March 22, 2020. Gallery hours are 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday, and entry is always free.

More from The Rice Thresher

ktru’s annual Outdoor Show moves indoors, still thrills

ktru’s 33rd annual “Outdoor Show” music festival shifted indoors March 29 due to concerns about inclement weather. Despite the last-minute location change, attendees, performers and organizers said the event retained its lively atmosphere and community spirit.

Rice’s newest sculpture encourages unconventional ‘repair’

A white-tiled geometric sculpture sits on the outer corner of the academic quad, between Lovett and Herzstein Halls. A variety of materials – string, pins, ribbon – are housed on the structure in plastic containers.

Review: ‘Invincible’ Season 3 contemplates the weight of heroism

When I think of "Invincible," I immediately picture Mark Grayson at the emotional center of his universe, much like Spider-Man anchors the Marvel world. Mark is a hero deeply shaped by tragedy, yet driven by a seemingly impossible desire to remain good. Despite pure intentions, his efforts often backfire spectacularly. And ultimately, despite his reluctance, he faces uncomfortable truths about what it genuinely means to be heroic.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication by The Rice Thresher.