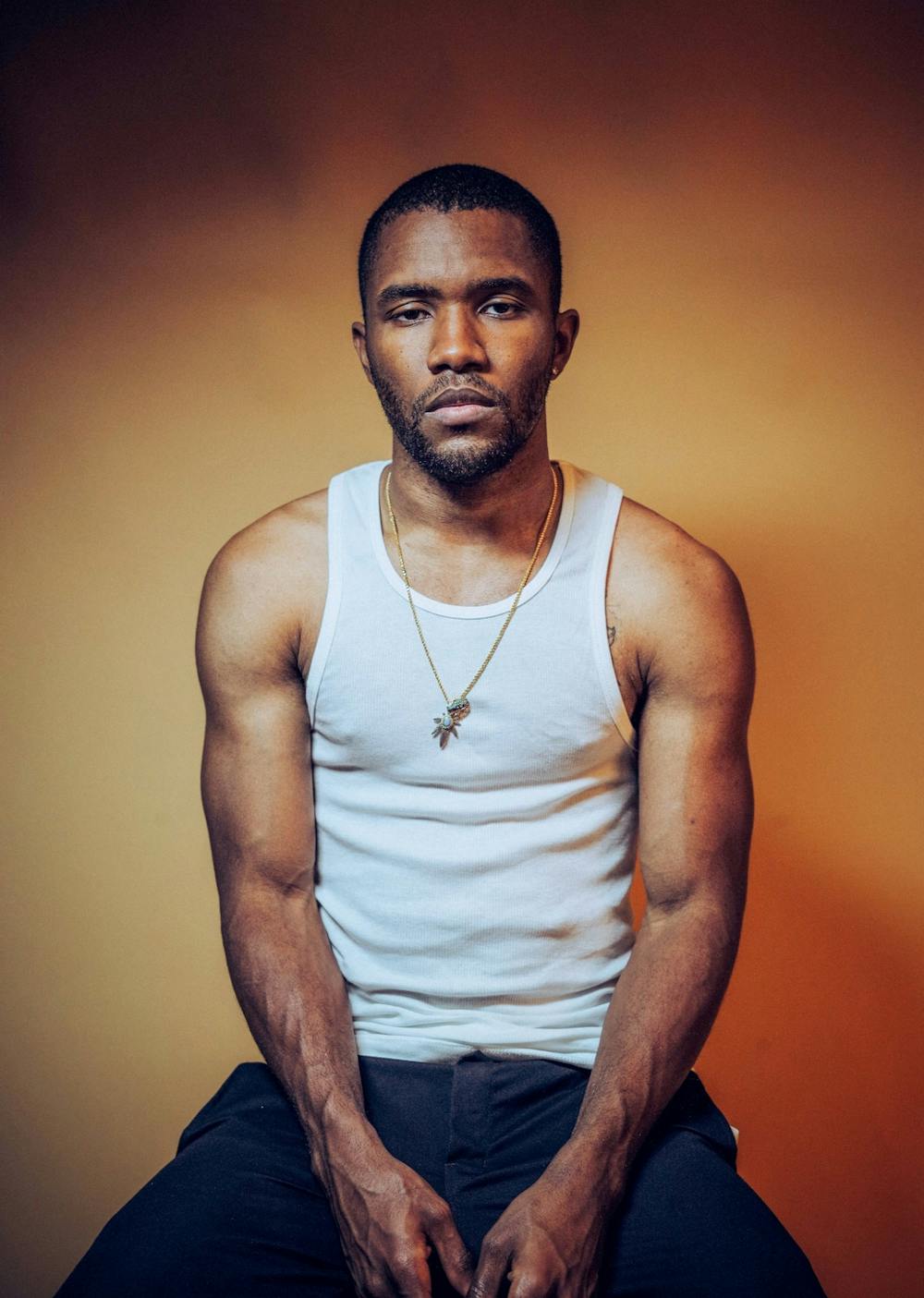

On Frank Ocean, Isolationism and the Vulnerability Paradox

Without a word or warning, elusive singer-songwriter Frank Ocean resurfaced from his sea of isolation this past Friday with the release of two new tracks, “Dear April” and “Cayendo.” Both intimate ballads stripped of rich instrumentation and centered around Ocean’s emotional vocals, the two tracks popped up out of the blue on Ocean’s website in October 2019 in the form of preorder vinyls which just shipped out last week, coinciding with the songs’ digital release.

Ocean has a penchant for the unpredictable. A year after dropping his first official album in 2012, “channel ORANGE,” Ocean seemingly slipped off the face of the earth. There were a few social media breadcrumbs over the next few years — a Tumblr post here and there, a captionless photo of Ocean in the studio uploaded to Instagram— but other than these ambiguous glimpses, Frank Ocean revealed little of his life over the next four years.

Then, in spring of 2015, a picture of two shiny stacks of magazines materialized on his website which he announced would accompany the release of his new album in July of that same year. But come fall of 2015 — still no album. This occured twice more over the course of the next year, with Ocean releasing cryptic messages and murky deadlines with the inevitable end result of no product. Finally, hours after a 45-minute video of Ocean constructing a staircase by hand surfaced online, his second studio album dropped.

“Blonde,” released in August 2016, is an intricately woven tapestry of gut-wrenching vulnerability, artistic intentionality and sensory splendor, a masterpiece created to be experienced alone. A nostalgia-drenched meditation on sexuality and sex, on love and heartbreak, “Blonde” — alternatively titled “Blond” to represent the album’s thematic dichotomy between masculinity and feminity — was clearly intimate in a way that “channel ORANGE” was not. Riding the wave of his 2011 mixtape’s rapturous reception, “channel ORANGE” was a portrait of a breakout artist in his early 20s enraptured by an entirely new world of decadence to which he had just been handed the keys. Though the album retains the thoughtful intricacy and detail of his mixtape “Nostalgia, Ultra,” “channel ORANGE” was made while basking in the limelight: “Blonde” was made during the following four years, trying to escape it.

Yet the more Ocean shunned attention, the greater his public persona (as The Artist Who Shuns Attention) grew. With each day that he refused to engage with the public eye, the speculative mythos constructed around Ocean grew a little stronger. Conspiracy boards popped up all over Reddit, fans became hyper-attuned to his every movement and even mainstream media outlets began to speculate. By removing himself from the limelight, Frank Ocean had become no longer just an artist — he was a cultural enigma. The stark contrast of “Blonde’s” vulnerability with Ocean’s isolationism, both preceding and following the album’s release, made one thing clear: the way audiences came to derive meaning from Ocean’s music was through the concept of his personal vulnerability.

This equation of value with vulnerability, imposed especially upon artists who remain private in other aspects of their lives, creates an inescapable paradigm in which the audience demands artistic vulnerability in exchange for personal privacy. Building a mythology around an artist’s personal choices about privacy often necessitates intimacy to validate their artistic outputs. This creates a paradox in which to satisfy our expectations, the unrevealing artist is required to produce hyper-revelatory art.

The implication of this paradox is important in how we interpret Frank Ocean and what we expect from his music. With “Blonde,” we came to define Frank Ocean by his intense vulnerability, imposing understanding onto his music solely through our high expectations of emotional rawness. Yet, it is both limiting and overly simplistic to equate the meaning in Ocean’s music with his own personal displays of intimacy. Ocean allows himself the space to create organically by existing outside of the public eye, but that doesn’t mean that the existence of this space is inherently what makes his music meaningful. The picture of Ocean as a reclusive artist with only his thoughts as company is incomplete, a mere outline of an artist whose depth and talent for storytelling extends far beyond the borders of his own emotional truths.

Ocean expressed his own frustration with this double bind in an interview with W Magazine this past September.

“The expectation for artists to be vulnerable and truthful is a lot, you know? when it’s no longer a choice,” Ocean said. “Like, in order for me to satisfy expectations, there needs to be an outpouring of my heart or my experiences in a very truthful, vulnerable way. I’m more interested in lies than that. Like, give me a full motion-picture fantasy.”

This struggle between truth and fabrication lies at the heart of a timeless question: What makes art … art? Is art powerful because of the truthfulness of the artist, or the perceived experience of the listener? Is art not equally valid when understood through the experience of the audience rather than through an understanding of the creator’s experience? When we create a cultural figure such as Ocean and place his artistic vulnerability on a pedestal, what we prioritize will therefore always be an almost morally-weighted expectation of truth. Yet this proves a limiting and incomplete way to understand any art, and Ocean’s in particular.

His two new singles are softly-worded answers to this question, an important page turn in the ever-unfurling tale of Frank Ocean. “Dear April” and “Cayendo” are some of the first products from this new period of Ocean, a period he’s made clear that will not be defined by his own emotional intimacy, complicating the relationship between artist and listener by shifting the vulnerability from himself to his audience. Two tales of heartache, the tracks engage with themes of infidelity and loss, muffled sonic soundscapes underpinning Ocean’s poetic vocals. Yet, the tracks’ artistic roots remain shrouded in the unknown.

By understanding Ocean’s music not as a personal diary but rather as a curated fantasy, we are able to elevate our own emotional experiences in the artist-listener relationship, opening up a new space of appreciation for Ocean as the multifaceted artist and creator that he is. “Dear April” and “Cayendo” are masterpieces, but not because of what they reveal about Ocean — rather, they’re masterpieces because of what they reveal about you.

More from The Rice Thresher

ktru’s annual Outdoor Show moves indoors, still thrills

ktru’s 33rd annual “Outdoor Show” music festival shifted indoors March 29 due to concerns about inclement weather. Despite the last-minute location change, attendees, performers and organizers said the event retained its lively atmosphere and community spirit.

Rice’s newest sculpture encourages unconventional ‘repair’

A white-tiled geometric sculpture sits on the outer corner of the academic quad, between Lovett and Herzstein Halls. A variety of materials – string, pins, ribbon – are housed on the structure in plastic containers.

Review: ‘Invincible’ Season 3 contemplates the weight of heroism

When I think of "Invincible," I immediately picture Mark Grayson at the emotional center of his universe, much like Spider-Man anchors the Marvel world. Mark is a hero deeply shaped by tragedy, yet driven by a seemingly impossible desire to remain good. Despite pure intentions, his efforts often backfire spectacularly. And ultimately, despite his reluctance, he faces uncomfortable truths about what it genuinely means to be heroic.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication by The Rice Thresher.