Review: “Antebellum” is not worth your time

Shortly after learning that Breonna Taylor's murderers were not indicted, I decided to watch “Antebellum.” I’d been avoiding it because I had no desire to watch a gratuitously violent depiction of Black female trauma, but I reasoned that that was why I needed to analyze it. I needed to put my thoughts together for people as to why these kinds of films need to be handled differently. In the context of President Donald Trump working to erase the realities and implications of slavery from the American consciousness, I am firmly in the camp that slave films do need to be made, but they need to be made differently.

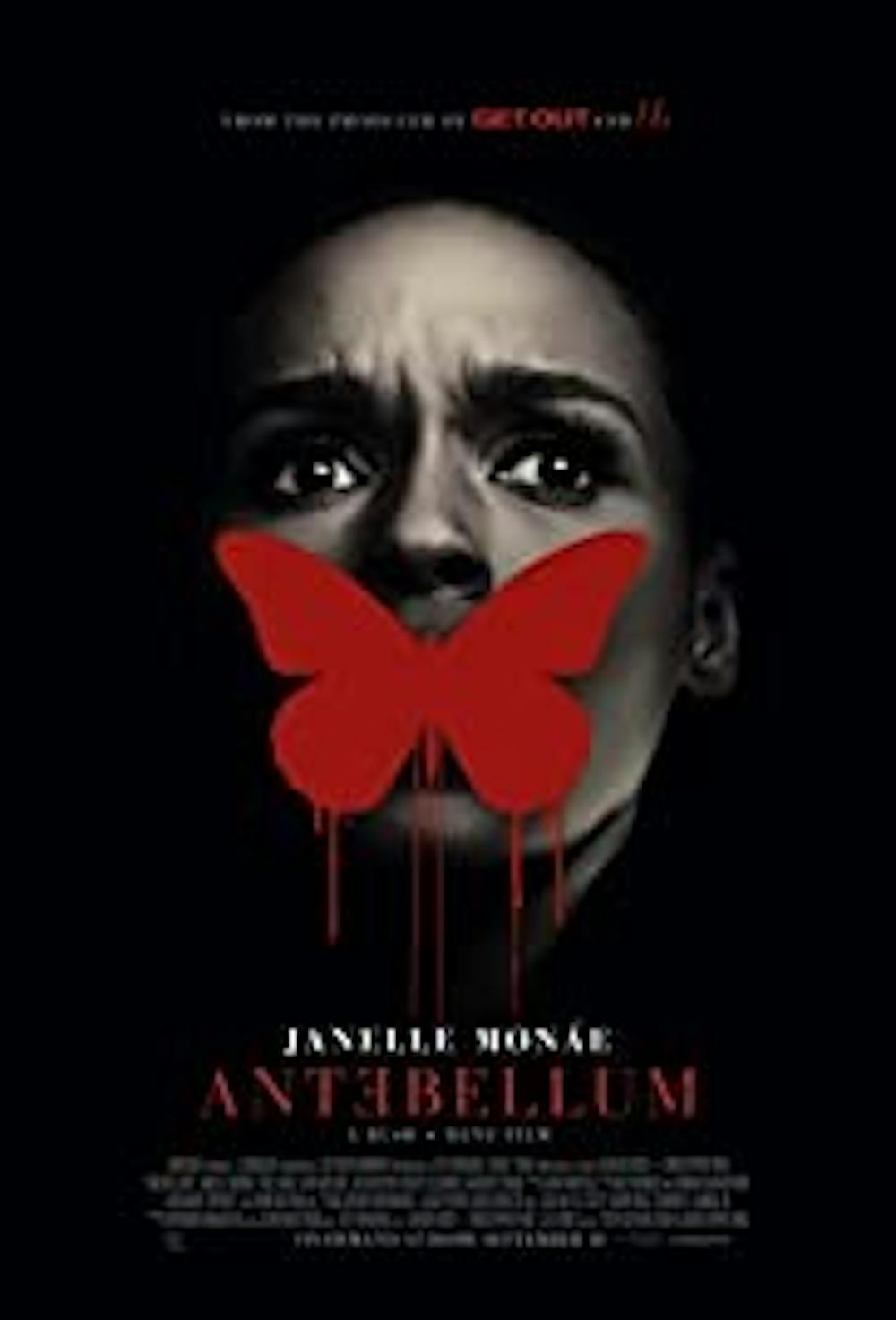

Marketed as a psychological thriller mystery tied to the producers of “Get Out” and “Us,” “Antebellum” seemed to be the story of a modern-day Black woman activist, Janelle Monae’s Veronica Henley, who is involuntarily transported back through time to a slave plantation. Filmmakers Gerard Bush and Christopher Renz set the intention that they wanted to do something new for the slave movie genre. My first impressions were of intrigue and suspicion.

I was suspicious of its marketing rollout because its trailer seemed so similar to the core premise of Octavia Butler’s “Kindred.” Butler is a world-renowned science fiction writer who has interwoven complex social justice themes into highly imaginative yet accessible stories. Lately, her stories have been interpreted as less of a social commentary and more as a prophetic vision of America’s future.

It would be an understatement to say that it’s ambitious for a film to tackle Butler’s writings, and even more egregious for a film to rip-off “Kindred”’s premise without attributing to her as inspiration in any way. That was when I began to assume the worst. My suspicions were indeed confirmed as Twitter, scholars and film critics, for the most part, were disappointed with the film.

The film begins with a panoramic view of an idyllic Confederate southern plantation setting. A little blonde-haired white girl enters the camera’s focus and gives her mother flowers on the staircase. Slaves turn from hanging white linens to smile at the soldiers passing by. A willow tree billows in the background in front of the slave quarters. A haunting and suspenseful instrumental persistently thrums on, hinting at the fact (made obvious from marketing) that something is amiss.

The camera moves past the slave quarters to white Confederate soldiers restraining a Black man and a Black woman slave. The camera zooms into her pain-stricken face and stays there until she decides to run. In slow motion, the soldiers chase her on horseback, and then one soldier lassoes her to the ground like cattle. She asks him to kill her, and he “obliges.”

In the film’s first moments, it prioritizes the aesthetic and perspectives of its white Confederate characters over that of the enslaved Black characters. This remains the case throughout the rest of the movie due to how the directors built the film around a gimmicky and poorly written plot-twist. Black characters in the film never become “human” to their audience. They are unnamed props and cryptic virtue-signaling mouthpieces for the film’s directors.

Not to mention their depiction of Black women is surface-level and stereotypical. Veronica and her friend Dawn (played by Gabourey Sidibe) are characterized as outspoken, strong Black women. The film does little to develop their vulnerability and interests outside of being pro-Black Lives Matter. So, they come off as insert-famous-Black-female-social-justice-warrior-here cardboard cut-outs.

The greatest fault of the filmmakers is that in their desperation to capture the aesthetics of “Gone With the Wind” and provide a social commentary on the dangers of white sentimentality towards the Southern Antebellum period, they fail to do the really complex and nuanced work of researching how to depict slavery without making a spectacle of Black pain and without centering the white gaze.

Similar to my commentary on “Queen and Slim,” this film’s underdeveloped writing and cinematic approach made the whole film feel like a perverse and performative work of social justice art. As an empty dramatization, “Antebellum” is a product of the times we are in: a time when social media influencers and celebrities proclaim themselves as allies and activists without doing the work because BLM is “trendy” and “brand-friendly” now. We are long past provocative and gratuitously violent depictions of slavery.

Modern-day lynchings happen every day, unfortunately, by the hands of white supremacist vigilantes and police. In the midst of social unrest and a global pandemic that disproportionately impacts women of color — and especially Black women — I task filmmakers to do more.

Deconstruct your own internalized anti-Blackness and center Black humanity in your art. We are beyond good intentions. Stop proclaiming that you are doing something new when your actions are perpetuating the old.

“Antebellum” is available to stream now on most platforms.

More from The Rice Thresher

Andrew Thomas Huang puts visuals and identity to song

Houston is welcoming the Grammy-nominated figure behind the music videos of Björk and FKA twigs on June 27.

Live it up this summer with these Houston shows

Staying in Houston this summer and wondering how to make the most of your time? Fortunately, you're in luck, there's no shortage of amazing shows and performances happening around the city. From live music to ballet and everything in between, here are some events coming up this month and next!

Review: 'Adults' couldn’t have matured better

Sitcoms are back, and they’re actually funny. FX’s “Adults” is an original comedy following a friend group navigating New York and what it means to be an “actual adult.” From ever-mounting medical bills to chaotic dinner parties, the group attempts to tackle this new stage of life together, only to be met with varying levels of success.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication by The Rice Thresher.