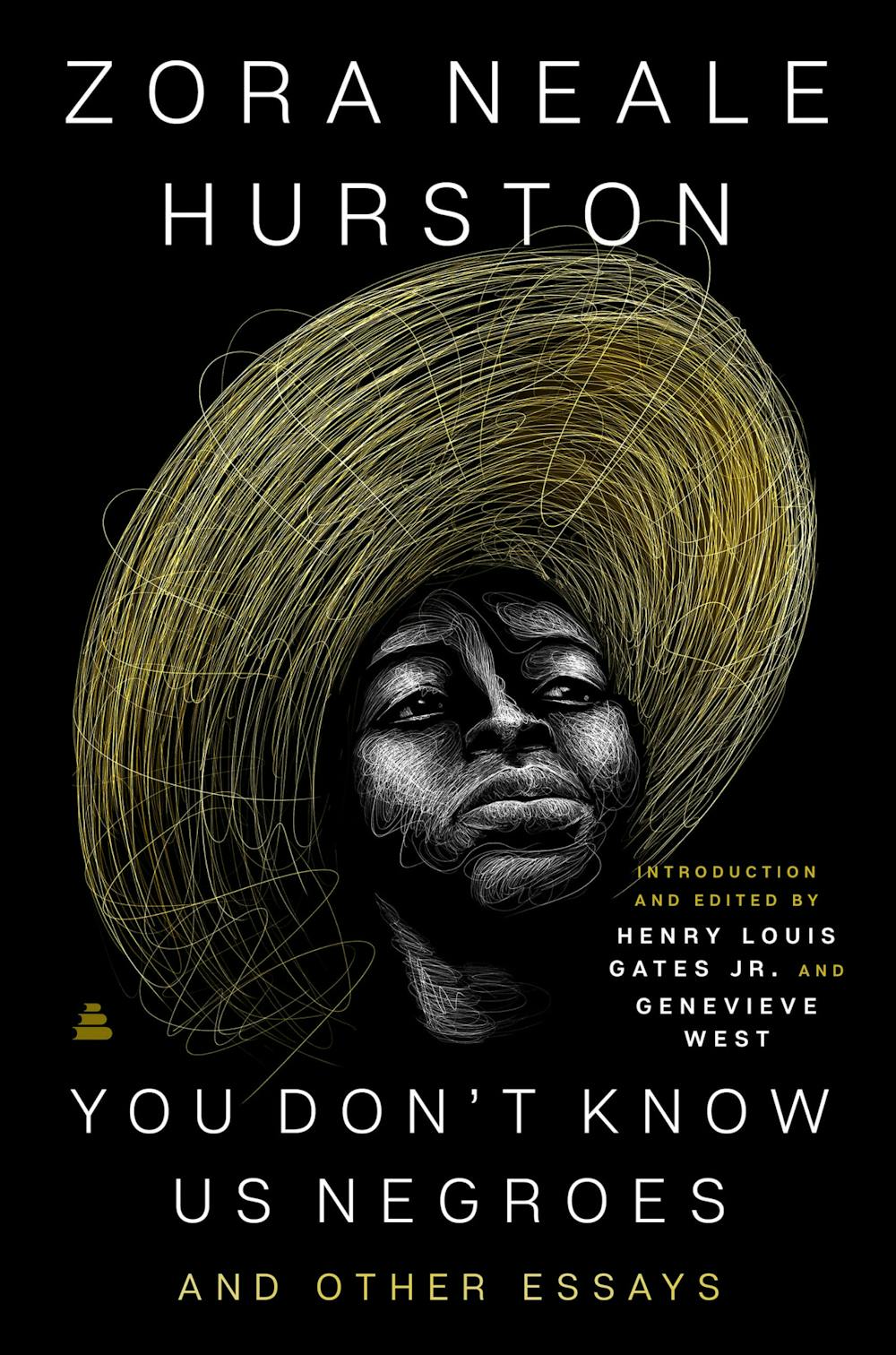

Review: “You Don’t Know Us Negroes and Other Essays”

Rating: ★★★★★

In “You Don’t Know Us Negroes and Other Essays,” Zora Neale Hurston powerfully establishes the immense contributions of Black culture and defends its worth. The collection, with an introduction by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Genevieve West, was released on Jan. 18, nearly 60 years after her death. It features essays that have never been published before, as well as several essays that are being reprinted for the first time.

It has been a privilege to read Hurston’s prose. In her more narrative essays like “High John De Conquer” and “The Last Slave Ship,” she uses elaborate extended metaphor and vivid storytelling to explore the hideousness of slavery. In “How It Feels To Be Coloured Me” her work is stark and clear as she explores Blackness. She writes that she “feel[s] most coloured when I am thrown against a sharp white background.” In “Bits of Harlem,” the opening essay of the collection, Hurston captures the infectious energy of the Harlem she knew, reflecting it in her writing style by incorporating sections of verse and song in her prose.

Coursing throughout the work is Hurston’s frustration and anger at the racist and demeaning way America has treated Black culture. Hurston artfully expresses herself in each of these essays, showing a command of the English language that few can rival. The collection’s title comes from an essay of the same name, which was published for the first time in the collection. The essay asserts the value of Black creativity, most notably through the use of a well-crafted extended metaphor that would be at home in the Odyssey. It also explores the hideous legacy of slavery. She writes, “Two hundred and forty-six years of outward submission during slavery time got folks to thinking of us as creatures of tasks alone … when in fact the conflict between what we wanted to do and what we were forced to do intensified our inner life instead of destroying it.”

The collection has immense breadth, ensuring that everyone can find essays that appeal to them. Many are incredibly informative — reviews of important books, commentary on the trial of Ruby McCollum, explorations of Black spirituality and critiques of the NAACP — while some are more narrative. Even these essays served a purpose — Hurston, through the act of recounting fundamental aspects of the Black experience, ensures that they are not forgotten. These essays wage a battle against the continued erasure of Black culture in this country.

The only complaint that I have regarding the collection is that many essays would be most appreciated if the reader already had prior knowledge on the subject matter. Furthermore, while Hurston’s very readable writing style ensures that this book can be read in one sitting, it would be best experienced if read gradually. There is no need to read them in order, so prospective readers should choose specific essays that appeal to them in the moment.

In “You Don’t Know Us Negroes and Other Essays,” Hurston asks us to recognize and appreciate the contribution of Black people to the nation’s culture. Her work itself demonstrates her point well — her essays are an important contribution to this country and its literary tradition.

More from The Rice Thresher

Study Abroad Photo Contest spotlights global experiences

For the first time since the Covid-19 pandemic, students gathered in the Ley Student Center to celebrate global experiences through photography.

Review: "The Crux" Should Redefine Djo

Joe Keery’s work has been boiled down to Steve Harrington from “Stranger Things,” but this label shouldn’t define his 10 years in the entertainment industry. Keery, under his stage name “Djo", is the voice behind the TikTok hit “End of Beginning,” which was released with his album “DECIDE” in 2022 and climbed the charts for the first time in 2024. With “The Crux”, Keery’s third album, he tries to separate his work as Djo and an actor, evidenced by the album’s visual of Keery escaping a building.

Review: “Lonely People With Power” merges blackgaze fury with dreamy introspection

Fifteen years into a storied career that’s crisscrossed the boundaries of black metal and shoegaze, Deafheaven has found a way to once again outdo themselves. “Lonely People With Power” feels like a triumphant return to the band’s blackgaze roots, fusing massive walls of guitar-driven sound with whispery dream-pop interludes, recalling their classic album trio of the 2010s (“Sunbather,” “New Bermuda” and “Ordinary Corrupt Human Love”). It also bears the learned refinements of “Infinite Granite,” the 2021 album where they dabbled more boldly in cleaner vocals and atmospheric passages.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication by The Rice Thresher.