‘Flipping over the rock’: Remembering students' fight against sexual violence

Editor’s note: This story contains mentions of sexual violence.

Three years ago, the Rice campus was enveloped by protests and discussions over the state of the university’s sexual assault policies. Partially lost to the mists of time and overshadowed by the pandemic a few months later, these protests are largely unknown to today’s student body after the numerous social disruptions these last few years have seen.

Origins of the protests

The protests were a reactionary spark to an anonymously published op-ed in the Thresher a month prior by Sydney Garrett, a Rice alum (‘19), who later came forward as the author. In the article, Garrett detailed how her rapist found a loophole in the Student Judicial Programs proceedings, delaying the hearings long enough to graduate a semester early, before a suspension could take effect. The op-ed was born soon after this discovery, according to Garrett.

“The combination of … my rage at how badly this was handled, and my rage [at] the way that the administration had treated me led me to write this op-ed,” Garrett, who had graduated the previous year, said. “[I was] seeking some payback or justice for the way that I had been treated.”

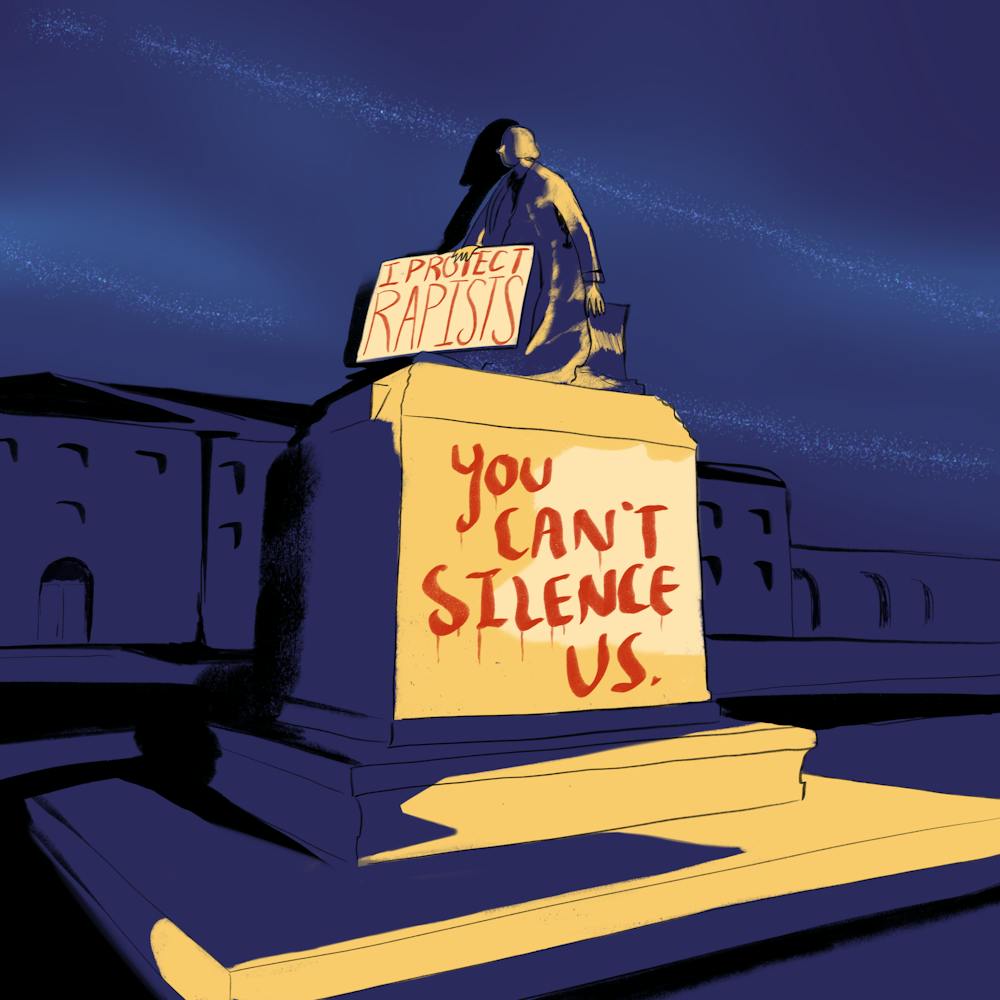

The protests occurred during Families’ Weekend in September 2019. The first outcries were on Sept. 26 and 27, according to the Thresher’s Oct. 2, 2019 issue, when a group of Rice students covered William Marsh Rice’s status with signs and staged silent protests in front of parents. According to Maddy Scannell (‘21), who served as the executive director of Students Transforming Rice Into a Violence-Free Environment from 2020-2021, students showed up to the protest wearing red and silently handed copies of Garrett’s op-ed to parents.

“Part of me still feels really bad; that was supposed to be a really exciting and fun experience for parents to see their kids, especially if it’s their first kid or something in college, to turn that into something very bitter and upsetting,” Scannell said. “But seeing the change in demeanor and opening up the eyes of these parents … was, I felt, so important.”

The decision to stage the protests during Families’ Weekend was intentional, according to Scannell. Students took advantage of the events to alert parents and hopefully put additional pressure on the administration to take action.

“Once you start getting things in print, getting things to parents who are your financial base and getting things to donors, that may make the school look bad, I think that’s really when people start to pay attention,” Scannell said. “If it means flipping over the rock and seeing all the scary things underneath it, given the choice, I think [administration] would rather not.”

The protests marked one of the first explicit displays of activism during her time at Rice, according to Scannell. Christina Tan (‘20), the then editor-in-chief of the Thresher, said that the scope of the reactions to Garrett’s op-ed was unexpected at the time.

“This was before George Floyd, before the massive protests of our generation. We didn’t think there was the appetite for that kind of protest or mass movement in the student body,” Tan said.

Garrett, too, said she was shocked by the fervor with which students reacted to her article, citing the protests as both a strange and validating experience as she witnessed her article being pasted up, handed out and protested with.

“[During] the process of being assaulted and then dealing with the repercussions of that, you really kind of get into this headspace of gaslighting yourself,” Garrett said. “It [was] nice to hear this vocal outcry from all of these people that I know, either closely or distantly, and have them reaffirm for me that it was messed up.”

She credited the op-ed’s anonymity for its ability to reach and resonate with swaths of the student body.

“Once I published it, it kind of became not my thing anymore. It was just this piece of writing that didn’t have a face or a name attached to it, so people [could] really take it and use it however they needed to or wanted to,” Garrett said. “This whole idea of being so mistreated by these people who were supposed to protect us was a very familiar feeling.”

Frustration with Title IX policy changes

In May 2020, eight months after the Families’ Weekend protests, the Department of Education announced changes to their federal Title IX policy, forcing schools such as Rice to make amendments to their own university policies. The momentum created by the protests and the cultural shifts in discussions about sexual assault provided students with an unprecedented role in the policymaking process, according to Izzie Karohl (‘22), who directed the Student Association’s Interpersonal Violence Policy Committee and served as an undergraduate representative on the Title IX taskforce.

“I definitely think that the collective student outrage about the op-ed helped make it a priority for the administration to include an undergraduate and graduate student on that committee,” Karohl said. “I genuinely don’t think that would have happened, had it not been for the protests to show that student perspective is important in structuring the sexual misconduct case process.”

Karohl has described her role in the policy changes as a bridge between student preferences and goals. She said her work largely entailed meeting with the executive committee of STRIVE, activists, survivors and people who had gone through Title IX cases, before giving feedback to administrators and pushing for policy priorities. Despite her involvement, Karohl said she felt the ultimate policy changes elicited mixed feelings from the Rice community.

“We wanted more genuine student and community feedback in that process. And it just did not happen. [It was] like a comment box on an email that no one saw,” Karohl said. “I think initially after the process, I felt like that was kind of intentional. I felt like they put that feedback box out so late because they didn’t really want the community feedback.”

Richard Baker, the university’s Title IX coordinator, countered some of the sentiments expressed by students at the time.

“I was surprised to learn that students felt that way,” Baker wrote in an email to the Thresher. “In addition to collaborating with students in the working group, I met with students weekly and participated in two student-led town halls and discussed the process. While I appreciate their frustration, we did take efforts to be transparent.”

A “culture of care”

Prior to the op-ed’s publication and the ensuing protests, topics of sexual assault and gender-based violence were rarely broached so openly, according to Scannell.

“We all kind of knew that there were rapists and people committing violence [who] were just on campus, going unchecked, especially graduating,” Scannell said. “[But we] didn’t know the extent to which that was enabled or facilitated by existing Rice policy, so that all that coming out was a shock to the system. Never so publicly had I seen someone being like, ‘This fucked up thing happened to me, and I’m pissed.’”

Both Tan and Aliza Brown (‘22) cited a failure in the culture of care — a key aspect of Rice’s self-described close-knit, community-oriented support system, often touted to prospective and current students alike — to keep students safe from violence.

“Before the protests, I felt completely alone in facing sexual assault on campus,” Brown said. “During O-Week, I was exposed to so much talk about a supposed ‘culture of care’ that I figured sexual assault was very rare at Rice. Because of the protests, I learned how wrong I was.”

Instead of protests and public conversations, discourse about sexual assault at Rice was largely governed by a “whisper network,” which Tan described as stemming from student-to-student gossip that helped make individuals feel safe about who they interacted with.

“I think a lot of women and queer people at Rice have a whisper network of sorts … I had heard so much already, just by being a student and being told to avoid so-and-so, or so-and-so walked in the room, and you’re like, ‘Oh, that person did XYZ,’” Tan said. “And I think that was a type of gossip that people used to survive and to make their own culture of care.”

Looking back on the years since these events, Karohl acknowledges a deeper sense of awareness and accountability that has pervaded the student body, but still points towards a stagnancy in the current discourse around sexual assault.

“I don’t want to say nothing’s changed. I think that people are a little bit more aware, via [Critical Thinking in Sexuality] and these protests, of the idea of consent and the idea of creating safer spaces,” Karohl said. “But I think we just have this very one-dimensional view of how [assault] happens and where it happens.”

Allison Vogt, associate dean of students and deputy Title IX coordinator, said that Rice has witnessed shifts in students holding their peers more accountable for problematic behavior. However, students such as Brown are still wary of how Rice’s cultural attitudes towards assault continue to evolve, citing a critical need for continual education on violence prevention.

“I was worried that new students wouldn’t understand the magnitude of the protests and what they meant: we, like most other campuses in America, are facing an epidemic of sexual violence,” Brown said. “Without this knowledge, community support and fervor to combat the issue, I fear that survivors at Rice could return to a more silent state.”

Tan said that one of the biggest challenges that the Rice community faces — and has been facing for decades — is a lack of continuity as each class graduates, creating a loss in activist momentum over the years.

“Something really interesting about Rice is there’s this four-year generational memory reset,” Tan said. “I think the thing I want people to do is remember.”

Editor-in-Chief Morgan Gage has recused herself from this article due to her position as executive director of STRIVE.

More from The Rice Thresher

New student center to ‘complete’ central quad

Breezeways, arches and outdoor seating will abound at the Moody Center Complex for Student Life set to break ground May 8. The 75,000-square-foot complex was designed by architecture firm Olson Kundig and has an expected completion date of fall 2027.

Family and faith: The West brothers share values on the field

When Robyn and Greg West enrolled their sons in T-ball, they said they saw baseball as a way to keep the boys out of trouble. Eighteen years later, brothers Graiden and Landon West compete at the Division I level for Rice’s baseball team.

Review: ‘Tamara de Lempicka’ fashions survival at MFAH

Houstonians first knew her as Baroness Kuffner, the mother of prominent socialite Kizette Foxhall, noted for her chainmail dresses and resemblance to Greta Garbo in the Houston Chronicle.

Please note All comments are eligible for publication by The Rice Thresher.